“We never feared drones until they killed Omar"

In September, a U.S. drone strike in Somalia killed Omar Abdillahi, a well-known clan leader local officials and residents say had supported the local government

We have a commitment to ensuring that our journalism is not locked behind a paywall. But the only way we can sustain this is through the voluntary support of our community of readers. If you are a free subscriber and you support our work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or gifting one to a friend or family member. You can also make a 501(c)(3) tax-deductible donation to support our work.

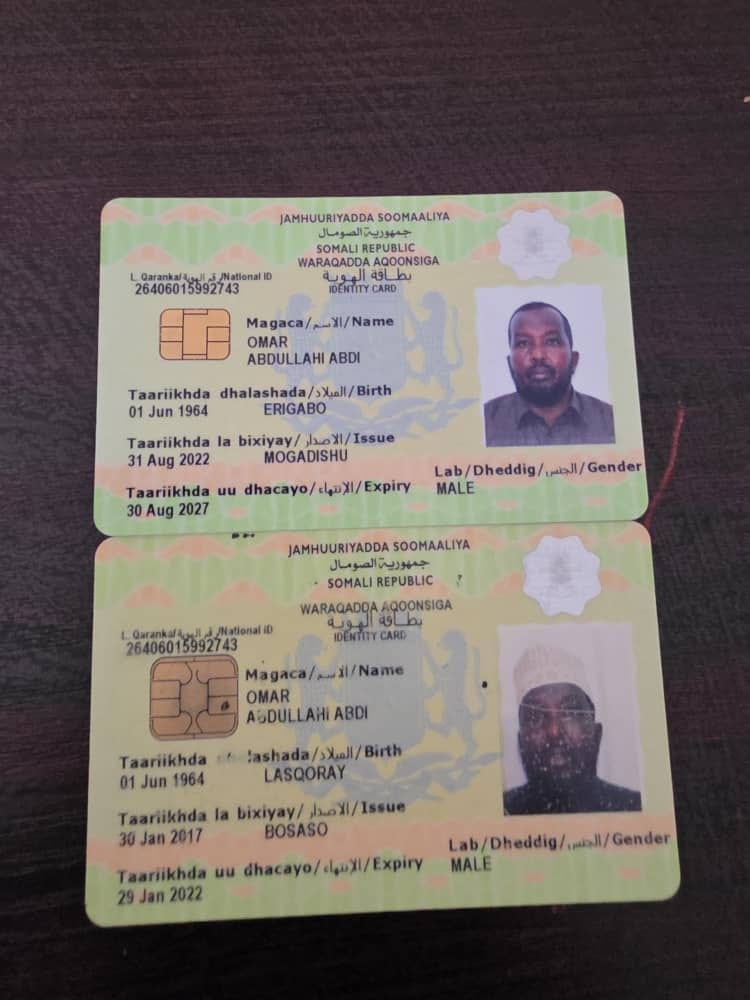

MOGADISHU—On September 13, Omar Abdullahi, a high-profile clan chief in Somalia’s Sanaag province, called his wife to tell her that he was on his way home from a nearby town, and to ask her to prepare dinner for the evening. Abdullahi was on the road back to Badhan, a remote town in the northeast of the country, returning to mediate a clan dispute, one of the responsibilities he held as a local community leader.

Abdullahi never reached home. On the drive back, his car was struck by three missiles fired by a drone overhead, incinerating his vehicle and killing him instantly. Only a piece of his stomach remained in the burnt-out wreckage, according to a death certificate seen by Drop Site News.

The strike shocked residents of Badhan and members of the Warsangeli clan that he hailed from. They had largely avoided the U.S.’s two-decade shadow war against the Al Qaeda-linked group al-Shabaab, and the Islamic State. Abdullahi himself was a prominent local elder, who residents and local government officials said was widely known and respected in the region.

Three months later, Asha Abdi Mohamed, Abdullahi’s mother, told Drop Site that she lives with the trauma of his killing. “I always have flashbacks of him being burned in a car. That is why I’m scared to sleep at night,” she said. “The soil under my feet was moving when I found out it was Omar who was killed.” Mohamed said that the drones continue to fly near Badhan; adding that she quietly prays for them to fall from the sky in order to be at ease.

Hawa Ahmed Ali, his wife, was waiting for him when Abdullahi’s sister suddenly arrived with the news that a vehicle had been hit on the road that he was traveling. She recalled that it was raining that day, a rare occurrence in Somalia’s harsh climate. “I didn’t want to believe it because I’m aware that other cars also travel on or use the same roadways,” his widow said.

Four days after the strike, the U.S. military’s Africa Command (AFRICOM) claimed responsibility for Abdullahi’s killing. AFRICOM claimed that it had acted in concert with the Somali government in killing what it described as an al-Shabaab arms dealer, adding that “specific details about units and assets will not be released to ensure continued operations security.”

Although the region, adjacent the Gulf of Aden, is a key smuggling route for weapons entering Somalia from the Middle East, interviews with local residents in Badhan and Somali government officials contradict claims that Abdillahi was an al-Shabaab operative or weapons dealer.

Omar Abdillahi Ashur is a commander of the Daraawish force, a specially-trained regional paramilitary unit that operates under the regional government in Sanaag. He knew Abdullahi since the 1970s, and said that he had in fact been a leader in fighting Somali Islamist groups in the area. “He was a backbone to resistance against terrorism,” Ashur said.

Somalia operates a federal system granting significant independence to its six member states, reflecting both the central government’s weakness and the strong local support many states command. Somaliland, in the northwest, though unrecognized, has declared independence. Puntland, one of the most autonomous Somali states, withdrew from the federal system in 2024 over election and constitutional disputes, and operates independently.

In the absence of strong state authority, respected elders like Abdullahi also play a vital role in local governance. Abdullahi rallied support against insurgents in Puntland over the years, and helped gather supplies for their government operations.

“His clan has suffered the most casualties in the fight against terrorism in this region,” Ashur said, citing battles against Somali Islamist group al-Itihaad al-Islamiya in the 1990s, and the deadly 2017 al-Shabaab attack on a Puntland base in Af-Urur that saw dozens of Warsangeli clansmen killed.

In November, Somalia’s outspoken defense minister, Ahmed Fiqi, said he would seek answers from AFRICOM about the killing of Abdullahi. Speaking in parliament, Fiqi said that although the intelligence that Somalia’s allies use for strikes is usually sound, there was no reason to kill Abdullahi, a public figure well known to authorities. “We could have called him and asked him questions,” Fiqi said. While Somalia has authorized allies such as the U.S. and UAE to support Puntland’s forces, he added, strikes in areas under its control are the responsibility of regional authorities.

Even al-Shabaab—the group Abdullahi was accused of belonging to—issued a statement denying he had ever been a member, saying U.S. allegations were used to cover up civilian casualties from the air campaign in Somalia.

In December, Puntland’s Police Force Criminal Investigation Department also released an official report into Abdullahi’s killing that contradicted the U.S. military’s claim that he was an al-Shabaab operative, a justification used for the strike. The issuance of the report pointed to unease within elements of the security establishment over the killing.

The report, which was submitted to both the Attorney General and Supreme Court of Puntland, found that Abdullahi had “no criminal record” and was not “under any investigation” by Puntland security or investigative agencies—explicitly challenging the U.S. assertion that the strike had killed an al-Shabaab operative.

AFRICOM did not respond to requests for comment about the report published by Puntland’s authorities.

“We Don’t Operate That Way”

The strike that killed Abdullahi comes amid an unprecedented escalation of the U.S. drone campaign targeting ISIS in northern Somalia, where the group is concentrated, and where al-Shabaab also has a small presence. Since his return to office, President Donald Trump has delegated authority to authorize strikes to AFRICOM commanders, which has increased their pace and aggressiveness. In comments to the Council of Foreign Relations just two weeks after Abdullahi was killed, Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud welcomed the move as “effective,” adding that the number of U.S. military assets in Somali airspace had also risen. (Drop Site News also recently reported on an airstrike in Jamame, a town held by al-Shabaab in south-central Somalia, that killed 11 people, including seven children.)

The U.S. conducted only one airstrike against ISIS fighters in the country during all of 2024. But to date in 2025, more than 100 have been registered across the country, the majority against ISIS—almost double the 51 airstrikes former President Joe Biden authorized during his term. The scale of these operations was underscored in May when the USS Harry S. Truman and its strike group launched what the Navy’s top admiral, James Kilby, called the “largest airstrike in the history of the world”, dropping some 125,000 pounds of munitions on targets in Somalia.

Referring to the strike that killed Abdullahi, but speaking more broadly about the unprecedented escalation of strikes in the country, a police commander in Sanaag who spoke to Drop Site accused the U.S. of “testing weapons on Somalis.”

Abdullahi himself was well known to the Puntland government. Just days before the strike, he had been part of a delegation that met with Puntland’s president, Said Deni, at Bosaso airport, where the U.S. military maintains a presence. Said Ahmed Jama, the governor of Sanaag province, confirmed to Drop Site that Abdullahi was among those leading a delegation during a meeting that lasted about four days—an engagement Abdullahi’s brother, Ali, said focused on Puntland’s impending operation against al-Shabaab in the Calmadow mountains, which is home to Abdillahi’s Warsangeli clan. Puntland, Ali said, was seeking Abdullahi’s support given his role as a key regional powerbroker.

The Puntland regional government did not respond to any questions about the strike.

Omar’s brother, Ali Abdullahi, added that if there had been allegations against him the U.S. and Somali authorities were more than capable of arresting him and putting him on trial instead of killing him while he was driving home. “The U.S. and their UAE allies all have a presence at Bosaso airport. He met President Deni six times inside the airport. He could have easily been arrested, but instead they [the Americans] decided to kill him.”

Puntland has not formally addressed the strike beyond the investigation by the security services, likely due to the sensitivity of U.S. security cooperation, though one senior official, speaking anonymously, distanced the administration from it. “We don’t operate that way,” the source told Drop Site.

“Still Searching for Answers”

Behind the escalation of the U.S. campaign against ISIS and al-Shabaab in Somalia lies a targeting process that multiple officials and analysts described as opaque and deeply flawed. Current and former Somali government officials who spoke to Drop Site said that once a target is identified, the U.S. requests permission to enter Somali airspace, and, when approved by federal authorities, drones can carry out a strike. Regional and federal Somali officials also often provide operational and other intelligence to support target acquisition, though U.S. officials have at times acted on their own intelligence as well.

One former senior Somali security source told Drop Site that, before Trump, the CIA coordinated with Somali officials and that the strikes ultimately had presidential oversight. The source said the process had more safeguards in the past, but that now the U.S. military was empowered to take the lead. “Military officials tend to be more gung-ho and mistakes are made.”

Samira Gaid, a Somali security expert with Balqiis Insights and former government security advisor, said that the standard practice was for Somali officials to receive “a call a maximum of an hour before a targeted strike” in which the defense minister would be asked to sign a letter approving the operation.

“Most of the time less,” she added, stating that the compressed timeframe made it difficult for Somali authorities to carry out their own assessments. “There is just an assumption that the U.S. knows best, that it has strong and accurate intel. But we know that that isn’t always the case.”

Adding to the impunity over civilian deaths in Somalia is a prior history of U.S. authorities downplaying civilian casualties from their operations, while rarely providing compensation for targeting mistakes. “The only time we see the U.S. admit to civilian casualties is when local elders make public outcry and when the media, and especially international media, catches on,” Gaid said.

Mursal Khaliif, a Somali MP and member of the US-Somalia Friendship Group in Parliament, was blunt in his assessment. “What is missing from the process of airstrikes, and how they’re carried out, is overall transparency and accountability,” he told Drop Site. “That needs to change.”

The problem, Gaid added, is that most strikes occur in areas controlled by al-Shabaab or other armed groups, making independent verification of their impact nearly impossible. “The onus then needs to be on the Somali government to check if these claims are correct because the strikes are usually behind the lines of al-Shabaab or areas that are inaccessible to partners.”

Governor Said Ahmed Jama told Drop Site that the strike has had lasting consequences for how U.S. operations in the region are perceived. “Everyone rose up and protested. Somalis both at home and in the diaspora condemned the American strike. We as the government officials, tribal elders are still searching for answers,” Jama said, visibly frustrated. The Warsangeli clan is demanding reparations from the U.S. following the attack.

Other security officials similarly believe that the U.S. drone strike that killed Omar Abdullahi has harmed perceptions of the U.S. among communities in the Sanaag region. “Everybody has their eyes on the skies. In the past, the war in Somalia was fought on the ground but now everyone’s attention is to the sky. It’s the new reality for many,” Darawish commander Omar Abdillahi Ashur told Drop Site News.

“These new realities can bring insecurity, lack of trust and ignite suspicion and resentment towards those involved in such activities,” he added.

Asha Abdi Mohamed, Abdullahi’s mother, said she continues to seek justice for her son. “The Americans admitted to killing him and we want answers for why they targeted our son and why they murdered him so brutally,” she said.

Her health has worsened since the strike, she said, and she struggles to sleep. “This was a peaceful region,” she added. “We never feared drones until they killed Omar.”

This piece shows how “precision” warfare collapses the moment accountability disappears. If a well-known clan elder who met regularly with Puntland officials can be incinerated on a public road based on opaque intelligence, then the problem isn’t just a single bad strike—it’s a system that treats Somali lives as expendable. Transparency, due process, and reparations shouldn’t be radical demands.

After the Vietnam debacle, research was conducted on the effect of the US air bombardment on the war. It turned out that air bombardment was a huge factor in increasing support for the North Vietnamese in the war against the US and the South Vietnamese government, I.E., air strikes are counterproductive. Perhaps the US Air Force command should revisit that old study.