“Hiding Behind Atrocities”

As Prosecutor Karim Khan seeks a flurry of arrest warrants, ICC staff accuse him of using court cases to dodge sexual abuse allegations.

I. A Cancelled Trip

The evening before Thomas Lynch was scheduled to fly to Israel last May, his boss contacted him. The trip, which had been weeks in the making, was off.

Lynch, a senior advisor at the International Criminal Court, was due in Jerusalem for meetings with high-level officials to finalize plans for a subequent visit by the head prosecutor, Karim Khan. That trip, during which Khan was set to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as well as visit Gaza, had been brokered with the help of the U.S. State Department, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken himself. The meetings, U.S. officials hoped, would give the Israelis a chance to make their case against potential charges. U.S. officials knew that it was inevitable the ICC would respond to mounting evidence of Israeli crimes in Gaza. But they hoped Khan’s trip would buy some time, if not stave off the prospect of arrest warrants against Israeli officials altogether.

The visit came at a delicate time: Eight months into the war, Israel had killed more than 34,000 Palestinians and, at the beginning of May, launched a ground invasion in Rafah, a city on Gaza’s border with Egypt where some 1.4 million Palestinians had sought refuge. Israel’s escalation threatened to exacerbate what was already a massive humanitarian catastrophe. Although the Biden administration had other tools at its disposal that it chose not to use—including a suspension of military aid to Israel—senior officials like Jake Sullivan and Brett McGurk hoped that brokering Israel’s conversations with the prosecutor might help “lower the temperature,” as one official involved in the discussions told Drop Site News.

Instead, on the day of Lynch’s canceled trip—May 20—Khan shocked much of the world when he announced in a CNN exclusive that he was seeking arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and then-Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, as well as three Hamas senior leaders—all of whom Israel has since killed.

“I have been saying repeatedly... to the parties to the conflict, ‘Comply now, don’t complain later,’” Khan told the network’s Christiane Amanpour that day. “It’s awful that in 2024 we have had to submit these applications to the judges of the ICC for warrants.”

The bombshell announcement immediately earned Khan and the ICC the praise of human rights advocates across the world, many of whom had long accused the court of failing to go after the most powerful war criminals. While it was unlikely that Netanyahu would ever sit in a courtroom in The Hague, the application for warrants was an unprecedented symbolic step to hold an Israeli leader accountable.

Human Rights Watch hailed the announcement as a “principled first step” by the prosecutor that reaffirmed “the crucial role” of the ICC. Amnesty International welcomed it as “a long-awaited opportunity to end the decades-long cycle of impunity in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) and to restore the credibility of the international justice system as a whole.”

But Khan’s surprise announcement, bypassing the heavily anticipated trip, was perceived by the Biden administration as a betrayal. Furious State Department officials who had helped broker the trip accused Khan of having “played them,” multiple U.S. officials and ICC sources told Drop Site. Blinken, who was to testify before legislators on Capitol Hill the day after the announcement, was particularly angry.

The Biden administration never engaged with the court after that. Khan “irreparably damaged any relationship he had tried to rebuild with the U.S.,” one source said.

The announcement also left Khan’s own staff at the prosecutor’s office astonished, including several who welcomed action against Netanyahu but felt that the case was not yet ready.

Several people at the office of the prosecutor told Drop Site that they were blindsided by the public announcement, a move they found abrupt and inexplicable. Some of those familiar with the case feared the applications themselves had been “rushed” and were “sloppy”, or at least not as strong as they should have been for a case of such import. “It didn’t feel like the timeline for a process where you're dotting every i and crossing every t, which you think for something this politically charged, that would be the priority,” one person said.

News of the warrants played out in public as that of the leader of an idealistic, if flailing, institution finally mustering up the courage to take a long overdue stand against Israel amid overwhelming evidence of its crimes. But behind the scenes a set of abuse allegations and Khan’s subsequent handling of them were about to plunge the court into a profound internal crisis at one of the most vulnerable times in its history.

While it wouldn’t become public knowledge until months later, less than three weeks before Khan applied for the warrants, a woman working closely with him had made serious allegations of sexual misconduct against the prosecutor to two colleagues. Media reports on the allegations—from the Daily Mail, The Guardian, the Associated Press, and others—have referenced instances of groping and other unwanted touching. But Drop Site has confirmed that the woman’s accusations were far more serious than what has been revealed so far, and include what she described to colleagues as monthslong grooming, psychological coercion, and sexual advances, which eventually escalated into “unwanted” and “coerced” sex that lasted nearly a year and continued even after she told Khan that his conduct had left her suicidal. The alleged acts include one episode, in April 2024, in which the prosecutor allegedly attempted to have sex with the woman while she pretended to be asleep in an effort to avoid him.

This account is based on interviews with more than a dozen ICC staff, as well as several others who worked closely with the court, and Biden administration officials. Everyone spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss an ongoing misconduct investigation, sensitive case work, or out of fear of retaliation. Drop Site also reviewed relevant internal documents, including emails, texts, phone records, written testimony submitted to investigators, and corroborated details of this narrative with publicly available and other sources.

Khan, whose conduct has been under investigation for several months now, was scheduled to meet with investigators for the first time earlier this week, after he canceled a previously scheduled interview last month, Drop Site has learned. An earlier probe, by the ICC’s internal oversight body, was quickly closed last May without investigators ever speaking with the prosecutor. Khan declined an interview request through a spokesperson for his office. The spokesperson did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this story. A spokesperson for the court declined to comment, citing the ongoing, “confidential” investigation.

The alleged victim, whose identity Drop Site is not disclosing, declined to comment on what she told colleagues but wrote in a statement to Drop Site News: “I want to spend this time, which has been highly distressing, to focus on my family. I have no other comment to provide.” Lynch declined to comment.

In May, after Khan learned that Lynch had reported the allegations internally, he instructed the team working on the Palestine case to move faster—a directive that they understood at the time to be related to political pressure in the midst of escalating Israeli atrocities in Gaza. In the two days leading up to the public announcement the staff working on the warrant applications came under “unbelievably intense pressure” from the prosecutor, a source said. Some felt they were asked to do the “impossible.”

"You can have a situation that deserves to be prosecuted to the full extent of the law, and you can also have a megalomaniac who has himself done something wrong."

Perhaps only Khan himself will ever know whether and how the misconduct accusations raised against him affected his decision to pursue the warrants for Netanyahu and Gallant when he did. But the timing, at a minimum, raised an appearance of impropriety with serious implications for the court’s reputation.

“The sexual misconduct allegations are very serious, need to be taken seriously, and need to be fully investigated,” one senior official working closely with the office said, noting that drawing a direct connection between the allegations and the warrants is impossible, but that Khan did nothing to dispel the impression that they were connected. “I think the prosecutor should have stepped down while the accusations were being investigated, because now the allegation is that he's actually using the office to sort of cover up.”

One of those questioning the timing of the warrant applications, once the initial allegations became public, was Sen. Lindsey Graham. In 2023, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Khan had launched an investigation of crimes committed there, eventually obtaining an arrest warrant for Russian president Vladimir Putin—the court’s highest-profile target at that point. Graham was one of the U.S. legislators who had rallied support for the court at the time. The U.S. had a long history of hostility toward the ICC, and Graham’s fellow Republicans had long opposed the court, particularly after an effort—which Khan dropped—to investigate crimes committed by U.S. forces in Afghanistan. At the time of the Ukraine probe, Graham and Khan’s interests had aligned. As the ICC began to investigate Israel, the senator privately met with Khan and received an assurance that no arrest warrants were forthcoming, according to sources at the court and messages reviewed by Drop Site. When the arrest warrants were announced, Graham viewed them as “egg on his face,” one person familiar with his reaction said.

In a letter to the Assembly of States Parties, or ASP, the body that oversees the ICC, sent days after the sexual misconduct story broke and first reported on by Fox News, Graham wrote that the timing of the warrant applications was “troubling.” “The abrupt decision to cancel this visit to Israel, along with these contemporaneous allegations needs to be explained, and I request full transparency on the matter to ensure there is no conflict of interest,” he wrote. Graham’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Once news of the allegations surfaced, staff within the prosecutor’s office also began to question whether the warrant applications were connected to the accusations against him. “It was completely inconsistent with the general approach that this prosecutor had been applying,” one person said, noting that Khan had normally prioritized engaging with those his office was investigating. “I haven't heard any explanation for why he did that, and the timing matches up [with the allegations]. It was suspicious. It was very reckless how it was handled.”

Others viewed Khan’s decision to seek the warrants as uncharacteristically “impulsive” before they learned of the sexual misconduct allegations, and “panicked” once they saw it in light of the allegations.

In the year since the allegations first emerged, Khan has remained determined to hold onto his job—even after a growing number of people, including several senior members of his team, repeatedly called on him to step aside while the investigation is ongoing. Instead, as a trickle of media reports has continued to come out, Khan has picked up the pace of his work. In recent months, the office has sought a flurry of arrest warrants, over alleged crimes committed in Sudan, Myanmar, and Afghanistan, while former Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, was arrested and transferred to the court’s custody. Last month, The Guardian reported that ICC judges ordered future arrest warrant applications in the Palestine case be kept secret, in what some at the court viewed as an effort to stop Khan from using the public announcements as a way to influence the case or bolster his own image.

Consumed by internal crisis, the ICC is also facing one of its hardest political tests yet. After the court issued the warrant against Netanyahu, several countries hinted that they may defy it, reneging on their obligations to arrest the Israeli leader and turn him over should he travel into their jurisdiction. Last month, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban announced that Hungary would withdraw from the court, just hours after Netanyahu arrived there, to which the ICC responded by initiating proceedings against Hungary. Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever followed suit, citing “realpolitik” to say Belgium would also refuse to arrest Netanyahu.

Many of those Drop Site spoke with said they agreed to do so because they see Khan’s departure, which he has staunchly resisted, as the only way to, in their view, “save the court.” Others noted that the court’s failings with regards to the allegations go far beyond Khan and said that the chaos he wrought is an indictment of the institution as a whole.

“We're an accountability mechanism with zero accountability ourselves,” one senior officer said. “On what planet does this type of allegation surface against the head of the institution and you have such a feeble response? For the court to survive there's going to have to be some serious reform, because right now, you have really one person in charge, who can have a profound impact on world affairs, and there's zero guardrails, checks, and balances.”

II. Palestine

The ICC was established by the 1998 Rome Statute and began operating in 2003 in The Hague, in the Netherlands, with the mandate to prosecute individuals responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and the crime of aggression. Today, it counts 125 member states, with some notable absences. Neither the U.S. nor Israel are members of the court, but Palestine, which was recognized by the UN as a non-member observer state in 2012, signed on to its jurisdiction in 2015.

Joining the ICC was the culmination of yearslong diplomatic efforts by Palestinian leaders who saw in the UN and the international accountability system their best chance to fight Israel’s occupation by invoking the rules-based international order. For years, they called upon the court to investigate Israeli crimes in occupied Palestinian territory.

Khan’s predecessor, Fatou Bensouda, finally launched an investigation in 2021, shortly before she left office. It was an historic announcement, at least symbolically. The U.S. and Israel rejected the ICC’s jurisdiction and vigorously condemned the investigation. But to the many countries who had long viewed the ICC as too feeble to stand up to the world’s most powerful, the announcement signaled the possibility that the court might deliver on its promise at last. For Palestinian leadership and civil society, it was a moment of enormous hope they might at last see some accountability after decades denouncing Israeli crimes. The Palestinian Authority at the time expressed “its great appreciation” for the ICC, with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas praising Bensouda for her “independence and courage.”

In practice, however, the Palestine investigation was barely staffed when Bensouda left. When Khan took over, he quickly developed a reputation as a forceful, if divisive, leader, and as a political player with an appetite for taking on ambitious adversaries. But while the Ukraine case had given him an opportunity to target Putin with European and American backing, going after Israel was another story. Although Khan indicated early on in his tenure that he hoped to “visit Palestine” one day, he did little to advance the investigation, which remained largely dormant. One person close to him said that the case’s controversial nature made it a “no-win” for the court, in Khan’s view.

Then came the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s ongoing, scorched-earth response in Gaza, which has so far killed more than 60,000 Palestinians—and likely many thousands more—, devastated the territory, and produced a monumental amount of evidence of possible war crimes and crimes against humanity, as well as growing, international consensus that Israel’s actions amount to genocide. Calls for the ICC to exercise its jurisdiction came almost immediately, particularly after Israel’s then Defense Minister Gallant ordered a “complete siege” of Gaza on October 9, 2023, with “no electricity, no food, no fuel” to enter the territory. Several international law experts noted at the time that Gallant’s comment that “We are fighting human animals, and we act accordingly” was possibly a declaration of genocidal intent and implied a policy of collective punishment—both crimes falling squarely under the ICC’s mandate.

Still, for three days, Khan’s office said nothing. They first addressed the Hamas attacks and Israel’s assault on Gaza in a statement emailed to me on October 10, in response to questions I had asked and confirming only that the court’s mandate “applies to crimes committed in the current context.” For the next weeks, as Israel’s campaign in Gaza intensified, Khan seemed to waver.

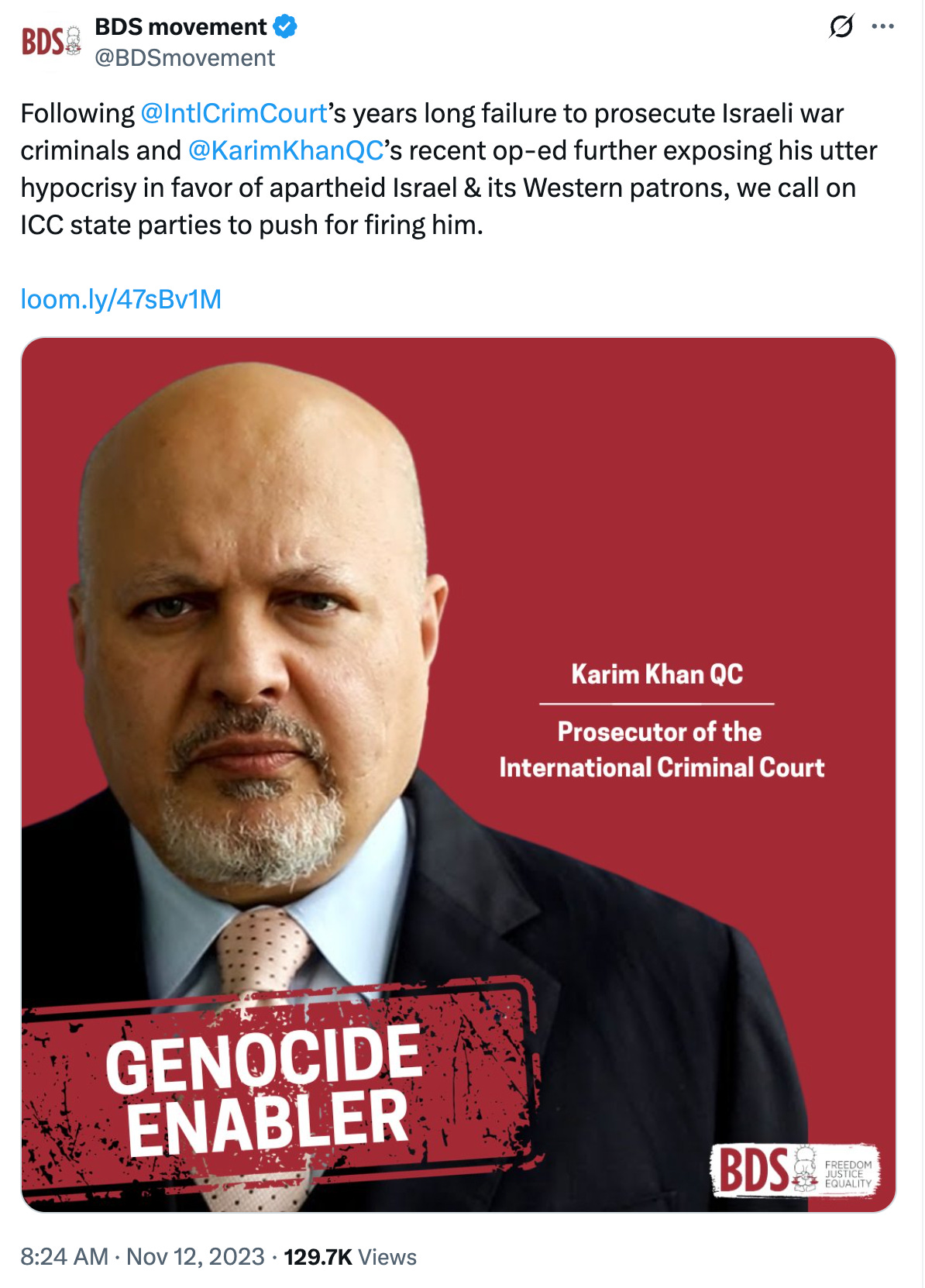

Those who had already grown disillusioned with the lack of progress on the ICC’s Palestine case soon began to criticize the prosecutor, noting that inaction over earlier Israeli crimes had paved the way for the impunity with which Israel unleashed its attacks on civilians in Gaza. In mid-November 2023, the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions initiative, a Palestinian-led movement with global reach, launched an online campaign criticizing Khan, complete with a photo of him with the words “genocide enabler” stamped on it. Khan was “very thin skinned,” a person close to him said, and “obsessed” with media coverage of himself. “He couldn’t handle it,” the person added. The viral campaign drove him “up a wall,” another echoed.

In late November, Khan visited Israel at the invitation of survivors and families of the victims of the Hamas attacks. While he also met with Palestinian officials in the West Bank on that trip, he did not visit Gaza, where Israeli forces had by then killed more than 17,000 people, and displaced a majority of residents. (Khan had previously visited the Egyptian side of the Rafah border, in October, but Israeli authorities denied him entry to the besieged territory.) Khan said at the time of his trip to Israel that the country had “a robust system intended to ensure compliance with international humanitarian law”—a comment that was widely condemned by rights advocates and some ICC member states, particularly in the Global South.

“A lot of states basically said to him, here is your chance to prove your legitimacy,” one source said. “It's easy to go against rebel groups in far-flung conflicts, it's easy to go after Putin when you have the support of most of the Western world, it's easy to go against all of these obvious figures, but here's a tough case. Here's where you prove yourself.”

Khan’s own staff and advisers also pressured the prosecutor, including Brenda Hollis, a deeply respected American attorney whom Khan had hired out of retirement to lead the Ukraine case, and Amal Clooney, a British-Lebanese human rights lawyer who had also faced criticism over her initial silence. Clooney ultimately became actively involved in the Palestine investigation, multiple sources said. She was the one who convened a panel of experts who issued a report on the day the warrants applications were announced. But after the applications were filed Clooney quietly stepped away—“she vanished,” one official at the court said. It’s not clear whether that was because she learned of the misconduct allegations, following backlash in the U.S. over the warrants, or for other reasons. She was one of about a dozen outside experts working with the office of the prosecutor who have quietly left their advisory roles over the last year; none of those contacted by Drop Site agreed to speak on the record. Clooney did not respond to a request for comment sent through a representative. Hollis, who has also left the court, did not respond to a request for comment.

By the end of 2023, more than three years after the Palestine case was opened, Khan began to move major resources into it, according to court sources, reassigning staff from the Ukraine case, including Hollis herself, and finally building up the team working on it more than three years after that case had been opened.

“His back was against the wall,” one source said. “He is not the savior of the Palestinian people that he's currently being presented as.” It felt, one person said, as if Khan was pushing forward with the investigation, “to stop people from criticizing him on Twitter,” another person at the court said. Others dispute that characterization and say that Khan was genuinely appalled by the mounting destruction in Gaza and felt a personal obligation to try to stop it. “I think he truly was deeply concerned about the substance,” one person said.

While Khan assembled the team that ultimately built cases against Israeli officials as well as Hamas leaders, he appeared to some of his staff hesitant about how to proceed. Privately, he told some of them that the arrest warrants could be filed but wouldn’t necessarily need to “go anywhere.”

Through the spring of 2024, Khan continued to both build a case against Israeli leaders and negotiate with U.S. officials, leading them to believe that no charges were imminent. His planned trip to Israel, he told them, would serve as an opportunity to evaluate how the Israeli government was investigating alleged crimes committed by its own forces, as the ICC’s mandate stipulates that the court cannot intervene when a credible justice process is underway at the local level. (The argument that Israel has a functioning mechanism to investigate its own forces has long been invoked by those seeking to dismiss calls for Israeli crimes to be investigated by independent bodies. But leading human rights organizations have questioned that—with the Israel-based B’Tselem announcing more than a decade ago that it would not cooperate with Israeli military investigations it argued amounted to a “whitewash.”)

Still, U.S. and Israeli officials hoped the trip would, as a Biden administration official involved in the conversations told Drop Site, “give Israel a chance at least to make its best case.” They also wanted to hold the ICC at bay as long as possible, and any action Khan might take against Israeli officials would come no sooner than a few weeks after his trip there, they understood.

Khan didn’t publicly explain what changed his mind about the trip, but on May 20, he announced the arrest warrants for Netanyahu and Gallant, over war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Gaza, including the starvation of civilians as a weapon of war, the intentional targeting of civilian populations, and persecution. He also announced warrants applications for Hamas’s leader Yahya Sinwar, senior commander Mohammed Diab Ibrahim Al-Masri, commonly known as Mohammed Deif, and political leader Ismail Haniyeh over a series of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in connection to the abduction, killing, and torture of Israeli hostages.

“We have a variety of evidence to support—not polemics, but evidence that’s been forensically analyzed,” Khan told Amanpour on CNN. “This is not some kind of emotional reaction to noise. We’ve been criticized for going too slowly, criticized for going too fast. It’s a forensic process that is expected of us as international prosecutors, as an independent court, to build evidence that is solid, that will not dissolve in the courtroom. And that’s what we’ve done.”

But some of those familiar with the details of the case say that the applications were not up to the typical standard of the office, which under Khan’s predecessor required evidence be “trial ready,” as one source put it, before warrants were sought. The court’s fastest case before then, another source noted, was the one built against Putin, which took a year and was carried out with full access to Ukraine, where the alleged crimes took place, and with the collaboration of Ukrainian, American, and other officials. In Gaza, where Israel has denied independent investigators access, the ICC had none of that, but the case against Netanyahu was assembled in “record time,” one person said, noting that “these cases require massive amounts of preparation” and the evidence assembled might not “stand up under scrutiny.”

The ICC panel of judges who reviewed the applications agreed with that sentiment at least in part, signing off on the warrants but striking out some of the allegations raised by Khan’s team. “On the basis of material presented by the Prosecution covering the period until 20 May 2024, the Chamber could not determine that all elements of the crime against humanity of extermination were met,” the panel noted.

“Despite the fact that real crimes are being committed and there is a lot of information out there, what is actual evidence that is admissible in court is a different thing,” one source said. “Even people who signed on to support the warrants didn't feel that comfortable that the evidence was all there to be doing it when he did it,” said another. “It was definitely more rushed and premature than planned.”

Khan may have been hoping the warrant applications would restrain Israel at a time when the violence it had unleashed on Palestinians in Gaza had reached an unspeakable scale. “He did genuinely have a deep feeling that every minute that he didn't move meant that he was culpable for not deterring further violence,” one person said. “And he thought that by taking action he could prevent things like Rafah from happening.”

But others felt that the rushing into applying for warrants so soon after being accused of misconduct created an impression that risks to severely undermine the court’s historic case.

“He tied his personal fate to the fate of a file,” one person said. “He is hiding behind all these atrocities, which is pathetic.”

III. The Sexual Abuse Allegations

The allegations against Khan emerged just over a year ago, when a woman who worked closely with Khan described the prosecutor’s serious and repeated sexual abuse to a female colleague with whom she shared an office. The alleged victim had not wanted to talk to anyone about it, but upon returning from a work trip with the prosecutor to Colombia and Venezuela, she had a breakdown. Lynch happened to pass by, saw that she was visibly distressed, and offered his help. She then relayed the allegations to him, as well. The woman—in what she would later call a “moment of weakness”—asked for help to establish some distance between herself and Khan, for instance by making sure they were never alone together and asking for overnight assignments on work trips which would give her an excuse to reject the prosecutor’s advances. She was terrified of Khan and of the possible consequences should a formal complaint be lodged, sources familiar with her account say.

But within a couple days of that meeting, Lynch decided that he had no choice but report the allegations to the court’s human resources department. The department referred the case to the court’s registrar, who in turn tapped the Independent Oversight Mechanism, or IOM, the body tasked with overseeing the ICC’s internal affairs, to initiate an internal review.

Before notifying them, however, Lynch also told two of Khan’s closest advisors. One of them, and the officemate, accompanied Lynch to Khan’s home to inform the prosecutor that Lynch was going to report the allegations. Sources at the court viewed the visit a “courtesy” to someone Lynch had worked with for years, going back to Khan’s previous job at the helm of the UN team investigating crimes committed by the Islamic State, or UNITAD.

When he heard the news, Khan grew visibly agitated, “like the oxygen was taken out of him,” according to sources familiar with how the meeting played out. He didn’t directly deny the allegations—instead saying that he had always been “nice” to the woman in question, asking why she would do this, saying that he might have “hugged” her, and offering that he was “finished” and would have to resign immediately.

As Khan processed the information, the advisor who had accompanied Lynch suggested that the timing of the allegations was “suspect,” as the Palestine investigation was heating up. Khan and his colleagues knew that The Guardian was about to publish an investigation detailing how Israel’s Mossad had sought to pressure and intimidate Bensouda, the former ICC prosecutor, as well as surveil Khan himself. Maybe, the advisor offered, the misconduct allegations were also part of some “Mossad” operation.

There was—and is—no evidence for such a claim. Even so, some people at the court questioned whether once they learned of the allegations, Israeli intelligence helped promote the story. A dossier about the allegations, reviewed by Drop Site, was sent to journalists from an anonymous email account, including the word “telephones” in Hebrew followed by the names and contact information for key witnesses. The allegations were also disseminated by anonymous social media posts. Someone made several attempts to hack into the electronic communications and other digital accounts of the alleged victim and some of her colleagues—actions that some sources speculated might have been the work of “state” actors. Drop Site could not independently verify any of these claims.

“They're capitalizing on it,” one source close to the court said, referring to Israel. “If you were a defendant in the case and you hear the prosecution’s lawyer did something unethical, of course you have a bit of a field day with it.”

Khan himself fueled the narrative that Israel might be behind the allegations. The morning after Lynch told him that he was going to report him, the prosecutor posted a cryptic statement on X, accusing unknown individuals of seeking to “impede, intimidate or improperly influence” the court’s work. In the following months, he repeatedly suggested someone was seeking to “interfere” with the court, and that he had been subject to “a wide range of attacks and threats”.

Although Khan’s first response upon hearing of the accusations was that he would have to resign, he quickly decided he would not. Khan may have calculated that stepping down would appear as though the court was caving to U.S. pressure over the Palestine case—something several member states would have rallied against, several people told Drop Site. They also believed that the looming threat of U.S. sanctions against the court—which the Trump administration ultimately imposed in February—would have turned Khan into a “martyr” in the eyes of some member states. “It will be harder to get rid of him because the states won't want to look like they're like kowtowing to U.S. pressure,” one person said.

Many at the court, including the alleged victim, also understood the abuse allegations were political dynamite and “a gift for Israel,” as one person put it, and they worried about how they may be used to discredit the ICC, and particularly delegitimize the case against Netanyahu, which many believed was warranted and crucial. “The Palestine situation has been deeply conflated with the allegations,” one person said. “And two things can be true at the same time. You can have a situation that deserves to be prosecuted to the full extent of the law, and you can also have a megalomaniac who has himself done something wrong.”

Instead of resigning, Khan quickly began to directly and indirectly pressure the alleged victim, who kept working at the office for several months, to recant the allegations in writing—a campaign first detailed by the Daily Mail. Some of those approaching the woman on behalf of Khan, including senior staff at the court, would try to talk to her sometimes multiple times a day. Khan’s wife, a prominent international attorney focused on women’s rights who sources say was deeply involved with court matters despite not being on staff, scheduled a last-minute meeting with the alleged victim within hours of her speaking with investigators, ostensibly about a work-related matter. A source at the court described that meeting as “unbelievable,” “inappropriate,” and a deliberate effort at intimidating the alleged victim and other witnesses.

A day after learning of the allegations, Khan’s close advisor threatened the officemate—a young, early-career staffer—suggesting that she and Lynch might face an investigation over their “motivations” for reporting the allegations. As soon as Lynch—who had always had a good relationship with his mercurial boss—reported the allegations, the prosecutor distanced himself from him. The morning after Lynch went to Khan’s home, Khan’s wife asked to meet Lynch for coffee and proceeded to repeatedly threaten him to spread a false rumor that he was having an affair with the alleged victim’s officemate, according to sources familiar with that interaction. That same night she again called Lynch, this time demanding he reassign the alleged victim to a different position at the court.

The following morning, Khan ordered Lynch and the officemate to leave for an unplanned work trip to Uganda. The two resisted going, both because there was no work-related reason for them to go at that time, and in light of the threats made by Khan’s wife.

Khan’s wife, Shyamala Alagendra, declined to comment on the claim that she made threats to Lynch, saying that the request she does so was “unnecessary and unwarranted.” She said her meeting with the alleged victim had been “scheduled in advance and involved other participants.” “At no point was I alone with the individual concerned, nor did I engage in any private or one-on-one conversation with her,” she wrote. “Her presence was appropriate and excluding her would have been both improper and potentially more concerning.”

By the time Khan abruptly canceled Lynch’s trip to Israel, less than three weeks later, their relationship had become irreparable, sources close to both said. Lynch and the alleged victim’s officemate did eventually travel to Uganda with another colleague, a few days after the prosecutor ordered them to do so. Upon their return, Lynch learned that he had been removed from the portfolio he had up until then been responsible for—what people at the court viewed as a demotion even though he kept his title and salary. The officemate, who declined to comment, was also removed from meetings she had been scheduled to attend and taken off her regular workflow.

While only a handful of people learned of the allegations in May, over the next several months, talk about them began to circulate at the office, where many were appalled to learn of Khan’s alleged misconduct, even as few were aware of its scale.

It all finally blew open in the fall. On October 17, an anonymous X account began posting information about the allegations, including details that appeared to be gleaned from the IOM’s short-lived probe and that identified the alleged victim by her initials, all but exposing her identity. That day, the prosecutor called the alleged victim—twice—in an effort to convince her to tell the Assembly of States Parties that she had made no complaint, according to evidence reviewed by Drop Site. Instead, she abruptly left the Netherlands and went into hiding for several months.

A day after the social media posts, the Daily Mail published the first of several stories about the allegations—and Khan’s denials. Khan never addressed the staff in person, but on October 24, the day The Guardian published another in-depth article, he sent an email to staff acknowledging the reports were “upsetting for members of the Office” and apologizing for not having addressed them earlier. “This is a difficult time for the Office in many ways,” he wrote, “and also a moment when we have never had so many looking towards us for action across situations.”

That same day, the president of the ASP, Finnish ambassador Päivi Kaukoranta, issued a public statement acknowledging the accusations and indicating that the IOM “was not in a position” to take the investigation further. On X, Khan publicly denied the accusations and pledged to continue to deliver on his mandate “no matter what actions are taken against me,” he wrote.

As the reports piled on, supervisors began fielding questions about the allegations from staff, and at an emergency meeting by about twenty Heads of Unified Teams—ICC lingo for senior staff—all but a handful spoke out openly against Khan, calling for him to step aside while the allegations were investigated—a rare show of resistance in an office in which even senior staffers had long feared their boss. “People are very scared of him,” one official said. “It was a big deal for people in a meeting with the deputy prosecutors to sit there and say, ‘Yeah, we think he should step aside.’”

Staff began to circulate drafts of multiple letters calling on Khan to step aside while the investigation was ongoing, and multiple senior officials, including Brenda Hollis, directly told him he should step down.

“For the good of the office, as a leader, it would have been an appropriate thing for him to take some kind of leave while there's an investigation,” one person said. “And at first he said, ‘I'll take it under consideration,’ but then he was basically like, ‘No, I'm not going to. You can’t make me.’”

“It was mortifying all those details coming out, and he just stood firm. I think he has a long game and his long game is, ‘They're not going to be able to get me out and I don't care if my staff doesn't like me, they haven't liked me for a long time, I’ll basically forge forward,’” the person added. “He's a very savvy person, he's playing chess.”

Khan was an unpopular boss: he ran the office as a top-down operation where his staff feared him and few felt safe questioning him. Among his most controversial policies was a requirement that staff working on a particular case be based in the field, which many staffers resented even as others argued it best served the work. Another was Khan’s push to force out a number of senior officials who had been at the court for years, including a couple who had themselves been accused of sexual misconduct. While some welcomed the moves as a much-needed breath of fresh air at a stifled institution, many saw them as an overt critique of his predecessor and veteran staff of the court.

"We want the court to survive, but part of wanting the court to survive is to make sure that it's an ethical institution."

Khan’s defenders say that staff who had long wanted him gone seized on the unproven allegations against him to stage a campaign seeking to remove him. One person close to Khan said that much of the staff had a “vendetta” against him over his abrasive style and changes he implemented at the office, and described staff’s response to the allegations as an attempted “coup.” Others more critical of him confirmed efforts to force Khan out but described the upheaval as a “mutiny” against a boss staff had once seen as an irascible “bully” and now viewed as an abuser that threatened to take the court down in scandal.

Since then, Khan has surrounded himself with a shrinking circle of loyalists and offering little guidance to staff as they navigate turmoil at the court, including U.S. sanctions.

But, according to several people, Khan and his supporters have also staged a smear campaign against the alleged victim, portraying her as “unstable” and “crazy,” “with a distorted view of reality,” as well as retaliating against some of those who had stood up for her. Court and U.S. sources said that Khan had thrown Lynch, his longtime adviser, “under the bus.” Lynch had previously expressed reservations about the arrest warrants against Israeli leaders out of fear that the political fallout would do enormous damage to the court. But those close to Khan painted Lynch as a “Zionist” and suggested he might have been doing the Americans’ bidding, encouraging other staff not to trust him. “There was an atmosphere created around him to try to explain away why he was no longer playing a central role,” one person said.

In February, Khan also reassigned two senior staffers who had been in charge of the Darfur case in what many at the office viewed as punishment for their support for the alleged victim. He also empowered those he viewed as loyal, including by giving a significant promotion to the advisor who had first suggested the alleged victim might have been working with Israeli intelligence.

At the office, Khan was nowhere to be found. “He was just keeping himself huddled up on the sixth floor,” said one staffer, noting that when Khan came in he restricted staff’s access to the floors where they work, something they say isolated him from staff and staff from one another. The office, multiple people said, had become profoundly “dysfunctional” even as Khan attempted to act as though it were “business as usual,” one senior officer said.

Meanwhile, U.S. sanctions against the ICC in retaliation for its charges against Israeli officials have made the work of the court much harder—including by making it a liability for American staffers to directly work with Khan, who has been personally sanctioned. At a time of compounding crises and enormous global expectations for the ICC, the prosecutor, many of his staff say, not only failed the court but dragged it deeper into chaos.

IV. Accountability

The turmoil has only deepened many staff members’ deep-seated disillusionment with the institution at large—and, in particular, with the court’s own accountability mechanisms.

Upon learning of the accusations in May, the Independent Oversight Mechanism, which oversees internal court issues, closed the matter in just a few days. In fact, it never formally opened an investigation at all, according to sources and text messages between investigators and the alleged victim reviewed by Drop Site.

IOM investigators first contacted the alleged victim on a Sunday, a few days after she had first spoken with Lynch and her officemate, writing in a text message that she had been identified as a “witness” to alleged misconduct and summoning her to an urgent meeting. That meeting, with two female investigators, happened at the bar of a hotel in The Hague that afternoon—while the alleged victim’s child sat at a nearby table with a babysitter, according to written testimony submitted to investigators and reviewed by Drop Site.

"We're an accountability mechanism with zero accountability ourselves."

The woman declined to proceed with an official complaint, and in subsequent texts with one of the investigators she asked for the “legal basis” for the IOM requiring her to speak; investigators had left her with the impression that she had “no choice” in the matter. Over the next few hours, investigators attempted to quickly coordinate a followup meeting. “Due to the serious nature of the allegations, we unfortunately cannot sit on them for too long and need to resolve the matter, balancing your interests and those of others and the court,” the investigator wrote in one message.

The woman asked that someone else join any possible follow-up meeting for “emotional support” and wrote that she felt “quite pushed” by investigators’ requests.“I would appreciate some consideration [and] care,” she wrote. “I would like for example, to take stock and to be able to process this.”

The investigator replied that the woman was under “no obligation” to meet with the IOM again if she didn’t want to and apologized for coming off as “pushy.”

By the afternoon of May 7, less than a week after the IOM learned of the accusations and after only having met with the alleged victim once, the investigator cited her wish “not to proceed with an investigation” and wrote to her that the matter would be “closed on our end.” In the message, the investigator also said the IOM had recommended a series of “mitigating measures,” including that the prosecutor “minimize one-on-one contact” with her.

The IOM never interviewed Khan.

When staff began to learn about the IOM’s handling of the allegations, over the following months, they were furious. Several people Drop Site spoke with said that it would be unthinkable in most other contexts for such serious allegations to go unaddressed, whether or not the alleged victim was willing to collaborate.

Some said the IOM was simply not equipped for something so “explosive,” and that its probe fell well behind regular standards for such cases. The oversight mechanism’s failures, they said, pointed to an underlying problem at the ICC, an “old world culture” where accusations of sexual misconduct against senior officials had been rampant since the court’s early days. Some pointed fingers not only at the IOM but also at the court’s registrar, Osvaldo Zavala Giler, who had first learned of the allegations in May but did not contact the alleged victim until several months later, when it became clear that journalists were about to expose the allegations. (The spokesperson for the court declined to comment on this).

By the fall, backlash against the IOM’s handling of the matter had grown so intense that the body’s head, Saklaine Hedaraly, sent a lengthy email to the court’s entire staff before he left his post in November. The IOM, he wrote, took a “victim-centered” approach in the matter, which requires “the consent of an alleged victim in order to proceed with an investigation.”

Hedaraly also argued the ICC had made progress in the handling of such allegations. “I remember when I joined the Court, some staff openly scoffed at the idea that elected officials could ever be held accountable,” he wrote. “I would invite you, therefore, to cherish and preserve the progress made in this area, not take it for granted, and help us improving our processes.” Hedaraly declined to comment further, telling Drop Site that the email “speaks for itself.”

Because the alleged victim “did not want to be involved,” a source familiar with the situation said, investigators concluded that there was nothing they could do. While the accusations were serious, investigators had no evidence or direct witnesses, and at a politically charged time for the court, they believed it would be premature and politically dangerous to accuse the prosecutor or ask him to step aside, the source said, citing concerns that the allegations could have been a motivated attack by “the Mossad or CIA.”

“What happens if an investigation said, 'There's nothing,’ you're gonna just bring him back?” the person added. “Many people don't like the prosecutor, they don't like his management style, he's a bit of a dictator. That doesn't mean that he sexually harassed someone—but maybe he did.”

That approach was widely condemned by other staff. “No investigation under normal circumstances requires victims’ consent in a situation like this, because you're actually incentivizing people to put pressure on victims not to cooperate,” one person said. Another described the process as “incredibly botched.” While many at the office believed the alleged victim’s claims, someone noted that even if they had not been credible, the IOM should have investigated how someone working in close proximity with the prosecutor had come to make them.

Instead, after the IOM declined to investigate further, those close to Khan began referring to it as having “cleared him,” and Khan seemed encouraged to stand firm. “Something flipped and he decided, ‘No, I'm going to fight this’, and I don’t know if that's just his natural bellicosity—he's a very aggressive lawyer, prone to really dramatic and reckless moves—or if somebody said to him, ‘you can beat this,’” one source said.

In mid-November, the Assembly of State Parties, the body representing the court’s member states, stepped in and launched an independent investigation. Since then, the United Nations Office of Internal Oversight Services, or OIOS, which is tasked with investigating internal matters within UN agencies, has been leading a probe, which has since sprawled into a review not just of the sexual abuse allegations—but also the claims that Khan retaliated against Lynch and others. When the investigation concludes, in the coming weeks, it will be up to the ASP to vote on how to proceed: it is the only body with the authority to vote to remove Khan.

As Khan awaits the investigation’s results, he has drastically picked up the pace of the office’s work. In late November, he announced he was seeking arrest warrants over crimes committed in Myanmar. In January, he announced he was seeking arrest warrants against Taliban leaders in the Afghanistan case, although the deputy prosecutor in charge of the case, Nazhat Shameem Khan, who sources say had been opposed to seeking the warrants because she did not believe the case was ready, declined to join Khan at the press conference announcing them. Nazhat Shameem Khan did not respond to a request for comment. A week later, Karim Khan announced he was seeking warrants against individuals responsible for atrocities in Darfur.

In March, Philippine authorities arrested former President Rodrigo Duterte and transferred him to The Hague, where he is charged with crimes against humanity over extrajudicial killings he oversaw as part of his abusive war on drugs. He will be the highest-profile official to be prosecuted by the court—and the first case brought by Khan to make it this far.

Khan’s critics say it’s difficult to separate the flurry of activity at the prosecutor’s office from Khan’s personal troubles. “He's running in every direction, maybe he's thinking, ‘I'll get done what I can get done,’” one person who has long been involved with the court said. “And I think he is responding to the public criticism of the office, that there are no cases.”

“Right now to save his reputation and also to put up smoke screens, he's releasing warrant after warrant,” echoed another. “But he's going after individuals who are never going to end up in the courtroom. And so he's going to come out of this having been in the media as the prosecutor who released X number of arrest warrants for high level individuals, but looking down the line three or four years from now, the courtrooms are still going to be empty.”

“We all believe in the mission, and we're trying to do our work, but the overall culture is dismal,” a third person said, noting that many have been taking extended leaves of absence to get away from a workplace growing increasingly toxic. “It’s very vertical, very demoralizing in many ways, and it takes its toll on people.”

V. What Happens Next?

When Khan was sworn in in 2021, as the third prosecutor in the ICC’s brief history, he promised to rescue an institution established as an ambitious project for global accountability but which had largely struggled to deliver on its promise. “The proof of the pudding is in the eating,” Khan said in his first speech as a prosecutor. “We have to perform in trial. We cannot invest so much, we cannot raise expectations so high and achieve so little, so often in the courtroom.”

Rights advocates and member countries that have long viewed the ICC as unwilling to take on the world’s most powerful have embraced the court’s more aggressive stance under Khan’s leadership. But navigating the inevitable political backlash, court insiders say, requires a leader who is unimpeachable and not distracted by personal considerations.

Khan was elected to a nine-year term but few, including those close to him, expect him to remain in the role much longer. Some say he hopes to salvage his political ambitions, which they say at one point involved seeking higher office in the UK government or within the UN system. But when and if he does step down or is forced out, Khan will leave behind an office in tatters, where many feel his actions have done irreparable damage and delegitimized the court’s work, even as he has turned it into the prominent geopolitical player it never was in the past. Many of Khan’s colleagues are especially angry about that: They view him as having squandered the court’s moral authority and credibility, undermined the cases they have spent years to build, and distracted from Israel’s crimes in Gaza.

“It is disgraceful,” a senior official at the court said.

“We have no desire to bring this place down,” another official said, a sentiment expressed by many of those who spoke with Drop Site. “And we know that much of this is going to be weaponized and none of us have any desire for this to be weaponized. We believe in the court, and we want the court to survive, but part of wanting the court to survive is to make sure that it's an ethical institution.”

Or, as another person put it, “Having all of this come out is the only way for the court to move forward with any integrity.”

If you have information to share related to this story, you can contact Alice Speri at alicesperi@protonmail.com.

What a baffling piece. In a long "Guest Post," whatever that is, Ms. Speri spends a lot of time repeating again and again what she said near the beginning. The use of accusations of sexual wrong-doing of one sort or another is a classic way of demolishing or at least tarnishing someone's reputation and are a favorite ploy of security agencies around the world, most definitely including the Mossad and the CIA. This post is a joy for Israel and the US, both countries being intent on the destruction of the ICC. Ms. Speri appears to be aiding and abetting in this destruction. With a sloppy post like this, Drop Site News has badly damaged itself.

That's sad. Sad for her and sad for the ICC. Khan should be held accountable, but so too should Netanyahu. After years of Trump trampling on US courts, and Netanyahu justifying 'collateral damage' in Gaza, this independent report by DSN on ICC culture is depressing - but it's what i signed up for. Thank you (I think)